Exxon and the Oil Giants Face the Carbon Future

Change is inevitable, adaptation speed varies.

This is a big story about what Exxon Mobil knows. But it’s also about what Exxon—and its peers in the oil industry as a whole—want investors, decision makers and the public to see about how their long-term business plans correspond to the climate future.

Whether they openly acknowledge it or not, every major oil and gas company is moving down the pathway to a warmer tomorrow with tighter constraints on carbon emissions. We can see this shift happening before our eyes. Eight of the 10 largest economies in the world have net-zero goals, and with the arrival of President Joe Biden that number will soon reach nine.

Institutional investors with trillions of dollars in assets see this, too, and that means they will insist on data about future emissions. It is data Exxon and other major oil companies have, although it is rarely shared with investors.

That disclosure gap might prove untenable. New facilities for extracting, refining, exporting or processing fossil fuel cost billions of dollars to develop and are based on financial projections that stretch out for decades. If the years ahead bring constraints on carbon, then that will mean today’s forecasts for future emissions are, in a very real sense, a powerful guide to future profits.

Higher potential emissions for any project could carry risk of lower earnings. And this transition risk applies to oil and gas companies as a whole.

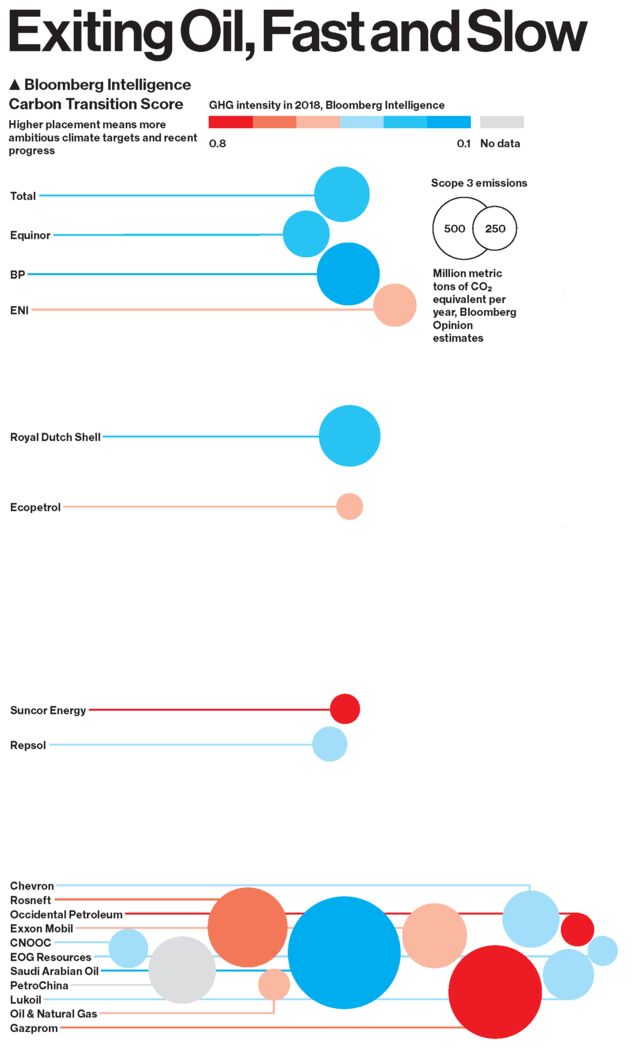

Above is a list of companies ranked by how readily they are adapting to a carbon-constrained world, based on analysis of climate targets from Bloomberg Intelligence. The analysts parsed disclosures from oil and gas companies, assigning each a BI Carbon Transition Score based on recent pollution trend, plans for 2030, and the gap between what a company is doing and what would be necessary to prevent global warming of more than 2C.

Nineteen companies are arranged vertically by this score, which weighs recent performance in cutting CO2 (25% of the score) and the relevance of their goals to the Paris Agreement (75%). France’s Total tops the list, meaning it’s adapting fastest.

“Companies that have not recognized the transition to the low-carbon economy as the most profound shift since the internet will be disrupted,” said Adeline Diab, who co-leads ESG investing at BI.

Those without climate goals, such as was the case for Exxon this year, score zero on the Paris-aligned portion of the BI Carbon Transition Score. Exxon this month announced it would change its approach to climate disclosure and for the first time release data about the planet-warming pollution from customers’ burning its fuels. The company also set a stronger target to reduce the emissions intensity of the oil and gas it extracts.

Those moves will likely affect Exxon’s BI Carbon Transition score next year. Casey Norton, an Exxon spokesman, said the new targets are “projected to be consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement.” Many analysts will try to determine if they agree with that statement.

In the chart above each company is color-coded to show its greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity, a way to assess climate impact in balance sheet terms. This is the measure Exxon has made the focus of its just-announced climate targets. An intensity measure considers Scope 1 and 2 emissions from a company’s operations and electricity use.

A recent project by Bloomberg Opinion compiled estimates for Scope 3, which covers climate pollution from a company’s suppliers and customers. Not everyone in the oil sector reports these figures. Russia’s Gazprom not only lags its peers in transitioning, as BI found, but also has one of the biggest Scope 3 estimates—meaning those emissions are unlikely to shrink anytime soon.

All assessments—by analysts, investors, policymakers, regulators and the public—are limited by the data that companies choose to disclose. Bloomberg Green’s investigative series on Exxon’s internal emissions planning has now demonstrated that oil companies have far more data on their future emissions than has been revealed to the world. If oil companies acknowledge they have this data, and shareholders with trillions of dollars can’t find it, that exposes a huge gap in disclosure.

Investors are now demanding climate disclosure from the oil giants. It could upend the transition ranking as it stands today, and change what we know about the oil industry’s approach to the planet’s future. —With Akshat Rathi, Eric Roston, and Dorothy Gambrell

More From Bloomberg Green’s Exxon Investigation: