Hooked

A raging heroin addiction fueled a former Boeing engineer’s yearlong, 30-bank robbery spree.

When Anthony Hathaway spotted the black SUV with the tinted windows, he was pretty certain the end was near. The guys blowing leaves across from the KeyBank he’d been casing all afternoon seemed a little fishy, too—because it was February in Seattle and spitting rain. But that could have been the heroin talking, so Hathaway wasn’t certain he was under surveillance until he saw the same black SUV pull into a parking lot, turn around, and pass by him again. “I just had a feeling,” he said later. “But for some reason I didn’t care.”

Hathaway drove to a nearby Burgermaster, parked the minivan he’d borrowed from his sister, and injected the last of his heroin. He stayed there for an hour, slumped over the wheel asleep, then woke up and remembered the day’s agenda. To make sure he wasn’t being tailed, he drove 5 miles north, and when he saw no more blacked-out SUVs or helicopters or suspicious groundskeeping crews, he headed back to the KeyBank, found a parking spot, and walked casually toward the entrance, like a guy who needed to speak with a loan officer. He wore khaki pants and a brown jacket with tan stripes and carried an open umbrella, though the rain had mostly stopped. He was unarmed, like always.

Hathaway slipped on latex gloves, pulled a mask over his face, and entered the bank at 5:25 p.m. with his umbrella still open. He yelled for everyone to get down, approached the only teller on duty, and asked for “large bills, fifties and hundreds.” Bank clerks are taught to comply with robbers, and this one did as Hathaway requested, handing over $2,310 in mostly loose bills. Hathaway stuffed the cash into his pockets and walked calmly out of the bank, less than a minute after he’d entered.

The law was waiting. Officers from multiple jurisdictions, including the FBI, intercepted him in the parking lot with guns drawn and put an end, after 30 robberies, to one of the most prolific bank-heist streaks in history. Hathaway, 44 years old at the time, didn’t hesitate or run. He put his hands in the air, lay down on the ground, and felt the world collapse upon him. He was scared of what was coming and also relieved that a long nightmare was finally nearing an end.

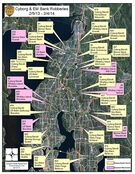

ROBBERY TOTALS AS REPORTED BY THE FBI

Hathaway grew up in Lynnwood, about 20 miles north of Seattle. He was a decent student and a pretty good kid. At 20, with just a high school diploma, he was hired by Boeing Co. as a technical designer in the galley systems group, doing mostly computer-aided design work, and went to work at the factory in Everett, which is the largest building by volume on Earth. Ten years into the job, he was promoted to engineer—the only person in his group to reach that status without a college degree, he says—and he thrived.

For 11 years, Hathaway flew around the world in business class, helping Boeing’s client airlines customize galleys. He became the engineering lead for galleys on the 747-8 Intercontinental, and by the early 2000s he was earning more than $100,000 a year, a good salary supplemented by profits of a drive-thru coffee kiosk he co-owned with his ex-wife and some partners.

Hathaway isn’t sure exactly when or how he ruptured a disk in his back, but he suspects it was during one of the roller-hockey games he and some colleagues played after work in the Everett plant’s vast parking lot. By 2005 the disk was so painful he sometimes couldn’t get out of bed. So he had surgery. Afterward his doctor prescribed OxyContin, which erased the pain in a way that nothing else could. “It was like a miracle drug,” Hathaway says—so miraculous he got hooked. He had a second back surgery, in 2008, and fell even deeper into an addiction he hid from almost everyone.

“It was really a couple years before I realized how bad it had gotten—when it got to the point where I needed more than my doctor was prescribing me,” he recalls. “I was peeling the coating off of the OxyContin, crushing them, and snorting them. I knew I was in trouble.” Eventually, he started smoking the Oxy, too.

The hole Hathaway was in kept getting deeper. The legitimate prescription his family doctor had given him wasn’t nearly enough, so he was supplementing it with a second script from a shady “pill mill” physician who was later arrested. That script cost him $150 every two weeks, plus an additional $600 to fill it, because his insurance was already covering the legitimate pills. Somehow, Hathaway was still designing galleys and flying regularly to Europe, but his first stop after the hotel was often a local ER, where he’d show his U.S. prescription and a Boeing ID in exchange for a fresh script to replace the pills he’d “forgotten” at home.

In 2010, Hathaway leveled with Boeing. He told a supervisor that he had a serious addiction and needed to go to rehab. The company, he says, was very understanding. “I took a month off, and I went away to a treatment facility,” he says. “On the way back, I stopped and got some more pills.” He resumed working but was now spiraling. “I didn’t let anybody know how bad things had gotten. I was ashamed and embarrassed. It’s living one day at a time, trying to figure out how to get out of this hell I’m living in.”

Here’s what hell looked like: Hathaway was now homeless and living in a Subaru Outback in the Boeing parking lot with his 18-year-old son, Conner, who was also an addict. Hathaway says 2010 was a pivotal year—that’s when Purdue Pharma LP, maker of OxyContin, changed the pill’s chemistry so it couldn’t be crushed into a snortable powder or heated into a vapor for inhaling. The new version had a time-release formulation; it was useless to addicts who were crashing.

“That is the beginning of the heroin epidemic,” Hathaway says, pointing to himself as living proof. He and his son began using heroin to get the same results they used to get from crushed Oxy. “It’s hard to explain to somebody who hasn’t been through it how it takes over your life,” he says. “The worst thing is the withdrawal. If I stop, I’m not going to work. I’m not eating. I’m not doing anything.” Addicts begin to schedule their lives in eight-hour increments, in fear of the crash. “Withdrawal sends you into such a terrible sickness that all you can think about is you got to get well,” Hathaway says. “It gets to the point that it’s not about being high, it’s about not being sick. I think that’s the thing that’s hard for people to understand. It’s really about not being sick.”

Hathaway took another leave from Boeing. He and Conner were now using several hundred dollars’ worth of heroin every day, and his salary wasn’t enough. They got desperate and in June 2011 decided, somewhat impulsively, to rob a bank. It was Conner who went inside. A dye pack hidden in the cash blew up as he left, leaving a bright red smoke trail to a getaway vehicle that someone saw him getting into. Police ran the tags and found him, holed up in a cheap motel with his dad.

Both were arrested, but only Conner was charged; the police couldn’t prove Hathaway had been involved. Regardless, he spent a few weeks in jail. That was the end of his career at Boeing—the company fired him for job abandonment.

Hathaway moved in with his mother, Kandy, who was gravely ill with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and on oxygen 24 hours a day. He became her caretaker and she his enabler. “She was hoping I could get some help, but there wasn’t anything she could do,” he says. The two of them lived off Kandy’s Social Security, plus food stamps. Hathaway somehow hung on and didn’t die, doing what he could to pay for his habit—until 2013. “That’s when I started robbing banks,” he says. “My mom’s living on Social Security and we gotta make ends meet, so I gotta try to do my part. I think I just justified it like that.”

Even at his most desperate, Hathaway had a moral compass that was operational, if badly bent. Many addicts steal from houses because it’s easy, but Hathaway couldn’t stomach that. “I don’t wanna make someone else’s life miserable just to try to make mine a little better,” he says. Banks seemed OK. “I figured that the money is insured, and I’m not really taking it from other people,” he says.

Bank robbery obviously carries significant risk, not the least of which is that it tends to get the attention of the FBI. But Hathaway says he wasn’t acting rashly. “It’s not something I just woke up and ran out and did one day,” he explains. “I started planning. I knew that as long as I didn’t leave any fingerprints or DNA or facial recognition that I should be able to pull this off without too many problems.”

One important detail: Tellers don’t resist. He knew this because his mom once worked in a bank and told him that she was trained to do whatever a robber asked. “I knew that you can go in there and you don’t have to have a weapon,” he says. “You don’t have to hurt anybody. They’re gonna give you money.”

The streak began at 1:40 p.m. on Feb. 5, 2013, at a Banner Bank in Everett, not far from the Boeing office where Hathaway had designed airplane kitchens for 22 years. He chose the location because it was rarely busy and right off of Interstate 5, providing rapid egress.

Hathaway had practiced for this, occasionally in front of his mom, who disapproved but was helpless to stop him. He rehearsed the movements, using the clock on the microwave as a timer to hone the process so he could get in and out in under 45 seconds. He experimented with disguises, especially his mask. He tried all kinds of face coverings before settling on a simple gray knit beanie that he could wear without looking suspicious, then pull down over his face until the fabric was stretched enough to see through. Simple but effective.

By the time he left home that day, Hathaway was “99% certain that I could get away with it.” Still, he was “extremely nervous” as he strolled into that Banner Bank—and then extremely surprised at how easy the actual robbery was. He’d parked the getaway car, a Ford pickup he stole from a guy who’d left it idling outside a pharmacy, at a Denny’s on the far side of the bank, so it was out of view for anyone inside. It didn’t matter if people outside saw him, because he removed his mask before he left and walked out casually, like a customer who’d just stopped in to cash a check.

Hathaway left the key in the ignition, so he didn’t need to fumble for it, and the on-ramp for I-5 was within sight, just across the intersection. All he had to do was pull out, turn right, and go. But when he turned right, the light was red. And not only that—at the same light, on the other side, was an Everett police cruiser. Hathaway froze. “I’m thinking, Are you kidding me? It felt like 10 minutes but was probably 20 seconds.” Then the light turned, and he drove calmly up the on-ramp and was gone. “I was so happy. I remember driving down I-5 thinking, I can’t believe I got away with that. I thought at that point this was so easy.”

The cop had been there by chance; he never hit his lights. And that taught Hathaway something valuable: “It takes a certain amount of time for them to get the call and respond.” He also learned that he should probably observe the sequence and duration of traffic lights. That way, he could be in his car and ready to go as they turned green.

He cleared $2,151, and got almost the same amount two weeks later from a Whidbey Island Bank in Mill Creek. This could work, he thought. So he devoted himself even more to the craft. A few robberies in, he had a nickname—the Cyborg Bandit, because detectives thought the knit mask was some kind of metal mesh—and a spot on a TV show, Washington’s Most Wanted.

Hathaway always tossed or burned the gloves, hoodie, and shoes he wore on a job, to eliminate DNA evidence and to be sure he didn’t repeat an outfit and give police and bank employees something to look out for. Same with cars. He didn’t ditch those, but he never used the same one twice. After the first robbery he’d realized he didn’t need to steal a vehicle; there was always an addict happy to lend out a car for a few hours in exchange for $100 or some dope.

To confuse police, Hathaway changed disguises. The second one was, in retrospect, ridiculous. He modified a T-shirt, cutting away the entire back so it was just the front hanging from the collar, like a janky homemade apron. He cut some eyeholes into this smock mask and wore it under a button-down shirt. As he prepared to enter a bank, he’d pull it up and over his face. Police called him the Elephant Man Bandit.

The third and final mask was a kind of hybrid. Hathaway cut the sleeve off a T-shirt, made two eyeholes, and wore it on his forehead like a headband—which he could pull over his face as he entered a bank. “It was definitely the best of the three,” he recalls. It was easy to make and deploy, and he could pull it down around his neck on the way out, letting him walk away without looking suspicious.

Once, he thinks it was about 10 robberies in, the bank slipped a GPS locator in with the money, but he found it while escaping and tossed it out the window of his car as he sailed down the freeway. Another time, Hathaway failed to notice that a bank had security glass, and the woman behind it simply refused his demands. “She just stood there and shook her head at me,” he says. He had no choice but to retreat—and fast. Then there was the time a woman sat in her car just outside a bank “breastfeeding her kid for like two hours,” Hathaway recalls. “That was interfering with me trying to get this done.” She finally left, and he robbed the bank at 5:57 p.m., three minutes before it closed.

Hathaway robbed five banks two times and two banks three times. The single biggest haul was $6,396 from a Whidbey Island Bank in Bothell, and the worst, $700, was from the Banner Bank where the spree started, on the third time he robbed it. Bank robbery was good, consistent work but also kind of a grind. “There was never enough money,” Hathaway says. “Every time I got money, we’re spending it”—mostly on drugs but also on rent and occasional trips to a nearby casino, as a treat for his ailing mom. Every time Hathaway hit a bank, he hoped he’d hit a jackpot and walk out with $20,000, but it never happened.

Hathaway robbed a bank once a week, more or less, for most of 2013, excluding a 67-day hiatus in May and June that caused detectives to think their elusive thief had been arrested for something else and was in jail. Not the case at all. He and his mom had merely ridden a string of good luck at a tribal casino north of Seattle and hit three jackpots, and more than $6,000, in a single night. “It was enough that I didn’t have to rob any banks for a couple months,” he says.

When Hathaway resumed in July, looking for targets began to feel like a full-time job. “I would spend days casing out a place, driving by, making sure they don’t have a security guard, and setting up my escape route—until I got comfortable with the whole plan. I’d usually do it towards the end of the day, when traffic was heavier.” Heavier traffic meant a slower police response and more cars to vanish among. “My main goal, though, was to make sure there were never customers. I’d sit there all day if that’s what it took to make sure there’s no other people in there.” If the situation called for it, he might jump on the counter and attempt to be menacing—like a bank robber from a movie. More commonly, all that was necessary was a quiet conversation with a single teller. They always complied.

As the months dragged on, the robberies got easier; the shorter days meant he could hit the banks after dark, and the Pacific Northwest’s never-ending rain allowed him to carry an umbrella, which was a great way to avoid being caught on camera as he approached. On the flip side, it got harder and harder to find banks that fit his criteria. More were using guards—there was a serial bank robber on the loose, after all. He had to drive farther and scout longer to pick targets. And he tried not to improvise, but shit happens. Hathaway robbed a HomeStreet Bank in Marysville in November, because it happened to be very near the Wells Fargo he’d been casing but couldn’t hit because of technical difficulties—as in, an armored car that lingered too long at the ATM. “So I just walked right past them and robbed the other bank,” Hathaway says.

For his 23rd robbery, on Saturday, Dec. 14, he tried something different. He brought an accomplice—a random junkie he recruited to stand inside the door as backup so he could jump up and over the counter and not worry about his back. The idea: to get more money in the same amount of time. “To be honest with you, I was really sick of robbing banks,” Hathaway says. “I thought if I could get 20 or 30 grand, I’d just go figure out my life and not be doing this shit.”

He got $6,120, which was great, but he had to split it, which wasn’t great. Also, a partner meant more risk, not to mention worry and whining.

The grind was wearing on Hathaway. And the addiction didn’t help. “Honestly, I got to the point where I didn’t really care as much,” he says. “I knew I needed help, and I couldn’t figure out how to get it, so I’m like, Yeah, I understand I could go to prison. If that’s what happens, that’s what happens. Maybe that’ll be what I need to get back on track.”

On the day of his 29th robbery, Hathaway spent the afternoon in Lynnwood casing out a Chase Bank he’d robbed a month prior. Located in a shopping area with a Fred Meyer grocery store, it was unusually busy. He just couldn’t find a time when it was empty. So he turned his attention to the U.S. Bank inside the Fred Meyer. “This would be a huge mistake,” he recalls. “I’d spent the whole year going out of my way to ensure no customers, and now, out of desperation, I’m about to break the golden rule that had contributed to my success. Furthermore”—and this is a big furthermore—“both of my sisters work at this Fred Meyer.”

Hathaway went in anyway and got $3,450 without incident—except that a customer followed him out of the store and saw him get into a light blue Honda minivan with a Seahawks sticker and a mismatched mirror. A light blue Honda minivan that belonged to one of those sisters.

Everett police put out an APB on the car, and a couple of days later a patrolman noticed it parked outside the duplex where Hathaway and his mom lived next door to his sister and her family. He was put under 24-hour FBI surveillance, police later told him. A week later, on Feb. 11, he saw that black SUV en route to KeyBank.

Not long after a Seattle police sergeant tackled him in the parking lot of that bank, Hathaway found himself cuffed to a desk inside an interrogation room in the Seattle Police Department’s robbery unit, on the seventh floor of headquarters downtown. Across from him were Seattle PD Detective Len Carver and King County Sheriff’s Office Detective Mike Mellis, veterans of numerous bank robbery cases and members of the FBI Safe Streets Task Force, formerly known as the Bank Robbery Task Force.

Hathaway was dead to rights, and he knew it. He sat slumped in his chair and answered questions politely, never once raising his voice or acting defiant. The detectives told him they’d been watching him “for probably much longer than you think” and that they knew this wasn’t his first robbery. “We did not stumble on you at KeyBank today because I happened to be driving through with a doughnut in my hand,” Carver said, according to a transcript of the interrogation.

“I’m a heroin addict,” Hathaway replied, then told them the story of his descent. “This opiate addiction … it just f---ed my life up.”

The two cops walked Hathaway through 30 robberies one by one, and he confessed to them all. Mellis later recalled for a report that Hathaway was “sad, crying at times” as the eight-hour interview progressed.

“I just wanted enough money to get outta here, to leave,” Hathaway told the detectives. “That’s what I told my mom. If I could just get enough money, I could go buy some methadone, and we could leave. We could get out of this environment for a while until I can get off this stuff and try to get back to work and get my life back.”

He warned the detectives that he’d be useless to them by morning. Withdrawal would be upon him, and he’d be “in the worst pain you can imagine,” he said. At the moment, though, he was lucid. “They’re gonna put me in prison. I don’t think it’s fair,” Hathaway said, which wasn’t the same thing as claiming he was innocent. “I knew when I left this morning, that I was taking this chance … I’m not gonna sit here and feel sorry for myself. I mean, it is what it is. I gotta man up and do my time.”

As the detectives walked him through the heists, they probed for details, and Hathaway was happy to divulge. He told them how he picked targets, the best time to rob them, and where to park the getaway car.

One of the things that most puzzled Carver and Mellis were the masks. Carver said he’d been sure the cyborg mask was made of metal. And the Elephant Man—what the hell was that? “Was it literally just a T-shirt draped over your head?” Carver asked. “I’ve never seen a guy just drape a T-shirt over his head and cut some holes in it.”

It was effective, Hathaway said, but imperfect. It was hard to cut the eyeholes in exactly the right place—the first time he wore the disguise he pulled the shirt up and couldn’t see anything. So he had to adjust the mask on the fly while trying not to panic.

Carver and Mellis chuckled. They’d seen this footage and wondered what the robber was doing. Carver placed a printout of a still photo taken from security cameras on the table. It was Hathaway in that mask.

“God, that looks ridiculous,” Hathaway said.

“You know what?” Mellis said. “I gotta say the first time we saw you do that we actually joked among ourselves.” This criminal with the sack on his head seemed … unimpressive. “We said, ‘You know, this guy’s gonna be easy to catch’—and here we are a year later still trying.”

“I spent a lot of time planning this stuff to not get caught,” Hathaway replied.

Carver wanted Hathaway to know that he’d made mistakes. He forgot about ATM cameras and had been photographed in profile more than once. He’d started to repeat some items of clothing—for instance, the red hoodie he was wearing at this moment. And then he used his sister’s minivan to rob a bank inside the store where she worked. After a year of careful robberies, leaving very few leads for cops, that one seemed especially reckless—stupid, even.

“The thought was, I need money for dope,” Hathaway said. “And every freaking bank I go to has security guards all of a sudden. It wasn’t that way when I started. I was having a hard time finding the right one. I wouldn’t just rob any bank; it had to be one that met the criteria I was comfortable with.”

Hathaway said he had a feeling he’d been spotted leaving Fred Meyer in the minivan. And while he hadn’t connected the two things at the time, he now recalled a flurry of police activity around his house a few days later. That was surely the day someone spotted the vehicle.

“You’re obviously shoddy near the end,” Mellis said. “It was one of the things that helped bring down your downfall, put it that way.”

Carver later told a prosecutor that the level of sophistication in these robberies was “greater than any other bank robbery that he had seen.” That Hathaway had never used a weapon or harmed anyone was likely to help him with the courts. The “lack of overt violence,” Mellis later told the local press, was “a point in his favor.”

“Was it too easy?” Carver asked Hathaway.

“Unfortunately, yes,” he answered.

Hathaway detoxed in a King County jail cell, vomiting for days into the toilet he shared with 20 men—until his delirious howls got so bad that the guards moved him to the hole in a suicide smock. When he came out the other side, Hathaway went back to the group cell and stayed there for two years, rejecting plea offers while writing briefs and pushing his various public attorneys to challenge the district attorney for a better deal. Finally, in 2015, he agreed to a plea. Hathaway pleaded guilty to four counts of first-degree robbery and one count of first-degree theft in exchange for eight years and 10 months. He had two years’ time served already and got three more for good behavior, which left basically four years, to be spent at the Monroe Correctional Complex, 45 minutes northwest of Seattle.

During those two years at King County jail, when he wasn’t writing legal briefs, Hathaway read “probably 100 books” and wrote the rough draft of his autobiography, which he titled I Fade Away. He wrote about the robberies, of course, but also about the unraveling of a life. “It’s really a painful story about a guy who pretty much had it made and lost it all because he became addicted to pain medication that he was prescribed to by his family doctor,” he wrote in an email from prison. “I deserve to be in prison for robbing banks. OxyContin took almost everything from me. I didn’t deserve that.”

When he transferred to Monroe from King County, the draft of his autobiography and all of his personal drawings and papers were lost.

For the past three years, Hathaway, now 50, has been living at Monroe with more than 2,000 other inmates. First he was “inside the walls” at the maximum-security prison, but after a year officials moved him to a minimum-security unit that everyone calls “the camp.”

Here Hathaway has a window that opens, a TV with 90-some channels, and a job doing maintenance in the Special Offender Unit, which gets him out of the camp from 7:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. five days a week. His pay is 42¢ an hour, with a maximum of $55 per week, and 20% of that goes to court fees and restitution for his crimes. The court ordered Hathaway to pay back $76,500, with 12% interest. “It’ll be around $112,000 by the time I get out,” he tells me during a visit in June. “But I have my whole life to pay it off.” A lawyer told him that as long as he makes payments every month, even small ones, he can apply later to have the interest waived.

In five years, Hathaway can claim his Boeing pension. He’s still the 50% owner of the drive-thru coffee shop, though it’s making less than half of what it did a decade ago. And he’s heard Boeing hires felons. “There’s a possibility I could go back,” he says. “But I’m not sure I want to work for a big company again.”

Hathaway will be free to walk out the prison gates on Dec. 23, but he may be leaving even sooner, perhaps sometime this summer if his application for house arrest with an ankle bracelet is approved. He’s already borrowed some money from his pension to help rent an apartment for Conner—who’s out of prison and working as a carpenter—Conner’s girlfriend, and their 4-year-old son. Hathaway plans to move in there to babysit his grandson while he figures out his next steps.

He’s been watching the backlash against Purdue Pharma as much as he can without regular access to the internet, and once he’s out, Hathaway plans to talk to lawyers and join a class-action suit against the company, if possible. “There are a lot of people like me that were prescribed Oxy for legitimate purposes, not knowing it was pharmaceutical heroin—not knowing how addictive it was. And lost everything. And when I say everything, I really do mean everything,” he says. He’ll be starting over with no job, no house, no car. He’ll almost certainly need a new career at 50.

Hathaway regrets many things, especially what the arrest did to his family. It was particularly humiliating for his daughter, who was then in high school. People at her school, he says glumly, thought he was one of the good dads. He also feels bad about taking that guy’s Ford truck before the first robbery. “Of all the shit I did, I think I feel worst about that,” he says. All of the man’s keys were on the chain. “I’m sure he was freaked out and had to change his house locks.”

And yet, Hathaway still thinks about banks—maybe too much. Movies can trigger it. Books, too. “Without question there is an amazing adrenaline rush when you run into a bank and jump up on the counter,” he says. “For a whole year that was my life. So I have to be aware. I fully plan on doing all the right things, and I’m confident that I’ll be successful. But if for some reason things went wrong, it would be way too easy for me to get back into it. Because I know how easy it is. I’ve done it 30 times. And that was on heroin. I think with a straight mind, things would have gone a lot differently.” He laughs. “Of course, I wouldn’t have been robbing banks in the first place.”

(Corrects timeframe in headline. Corrects location of Chase Bank in section three, paragraph 18. Corrects robbery totals based on data from FBI.)