China Wants Activists to Stay Out of Its War on Pollution

Citizen activism in the mold of Greta Thunberg is all but taboo in the world’s biggest polluter.

When Premier Li Keqiang declared a “war against pollution” in 2014, a few hundred residents of the city of Wuhan in central China took it as a cue.

They printed Li’s words on a six-meter (20 foot) banner and protested outside a foul-smelling incinerator plant they feared was causing illness in the community. Buoyed by the conviction they were answering the leadership’s call, the residents were instead harassed by local police officers who tore down the sign and trampled on it.

“We were worried and angry when we realized what was causing the stench and making our kids sick,” said Zhang Xijiao, 44, who was detained for a week for making the banner. “But we are like ants, the local government can crush us as they please.”

The episode kicked off a six-year fight that has seen Zhang harassed and monitored by the local authorities, with no sign that the government plans to relocate the incinerator despite her repeated petitioning and posting on social media about the pollution.

China is vaunting its climate credentials as it seeks to clamp down on environmental damage at home and demonstrate a commitment to the international order derided by U.S. President Donald Trump. Beijing has signed up to the Paris Agreement, spent big on clean energy, announced curbs on single-use plastics and made real progress in tackling air pollution. Yet what has become a key driver of the climate agenda globally—activism as popularized by Greta Thunberg—is all-but taboo in China.

One of the paradoxes of the Chinese system is that even as President Xi Jinping has made fighting pollution one of his main goals, civil society has been greatly restricted under his rule. That leaves little room for public discourse and open criticism of government policy.

The fact the issue is championed by the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao makes it all the more delicate, prompting local officials to try and silence activists who could expose environmental degradation happening under their watch.

Indeed, the eight green activists interviewed for this article said that it’s becoming increasingly common for non-governmental organizations, both domestic and foreign, to avoid sensitive topics altogether and to practice self-censorship so that they can keep operating in China. Most asked not to be named to avoid attracting official attention.

As the campaigning residents of Wuhan found to their cost, pushing back against the authorities is a serious matter. More recently they switched tactics to try and draw the central government’s attention to their plight. But according to Zhang, Wuhan officials have blocked their attempts to reach Beijing, monitoring when they book tickets to travel to the capital.

▼

In September last year, a group of five residents made it to Beijing to petition officials—only to find that word had been sent on ahead. They were met at the train station by about a dozen young men dressed in black, who said they’d arranged for them to see some officials to discuss the issue, and ushered them into three cars. Instead of taking them to a government building in the capital, the cars drove them all the way back to Wuhan, a journey of more than 10 hours.

Zhang—who spoke before the current outbreak of an unrelated virus in Wuhan—reserves her scorn for the local authorities and what she regards as their lack of willingness to protect people’s health. “The unexpected kidnapping made me lose faith again in the local government and how unreasonable they can be,” she said.

China’s 1.4 billion people produce growing mountains of trash that urgently need to be dealt with. According to the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, the volume of treated domestic garbage in urban areas reached 215 million tons in 2017. State media often cite a figure from the Urban Environment and Sanitation Association of nearly 1 billion tons of waste each year.

A pilot recycling program took effect in Shanghai in July that will expand to 46 mega-cities by the end of 2020. The results so far have been mixed though, as the four-tier, color-coded garbage sorting law stumped residents. Until recycling takes off, landfill or incineration remain the only ready alternatives.

The China model of environmental protection “has been cautious about too much organized society participation,” said Alex Wang, a law professor at UCLA who used to work with green NGOs in Beijing. “The Chinese government is basically betting that they can do it through a state-led, even state-dominant, approach.”

China consumes about half the planet’s coal and is the world’s biggest polluter, yet its anti-pollution drive is yielding tangible results. In 2019, the average concentration of harmful PM2.5 particles in Beijing fell to the lowest since the U.S. State Department started publishing readings from its embassy in 2008. The reading was still almost five times the World Health Organization’s recommended level, but China has effectively handed off the baton of home to the world’s most polluted cities to India.

That relative success is unlikely to lead to more acceptance of environmental activism. In 2017, the government enacted a law requiring foreign NGOs to partner with Chinese groups and submit projects for approval before executing them. In practice, that often leads to self-censorship as environmental bodies try to skirt what’s out of bounds.

▼

Some activists have learned how to work around the restrictions. Beijing-based Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, one of the country’s most prominent green NGOs, targets big private companies from Walmart Inc. to Huawei Technologies Co. to push for more sustainable manufacturing practices and communicates frequently with the Ministry of Environment and Ecology rather than confronting the government directly.

“The environmental area is where Chinese society has the biggest consensus,” said the institute’s founder, Ma Jun. “The most important work for NGOs is probably to find out where is the boundary, and how to make a substantial push within limited space.” Greenpeace, the biggest international environmental NGO operating in China, ditches its signature model of organizing non-violent protests and instead cooperates with the government through different channels including providing policy feedback. The organization is still waiting for official registration in China years after applying.

Local governments can also put enormous pressure on smaller NGOs.

“Local authorities think of us as troublemakers for bringing them more work,” said Zhang Jingning, who runs the Wuhu Ecology Center in Anhui province, which advocates for more environmentally-friendly incinerators across China. “Individual cases are sometimes sensitive and we don’t want to get involved in conflicts.”

Zhang’s organization pushes for more transparent information disclosure by companies operating the plants and writes reports on how well regulators have carried out their supervision of the incinerators. The center reached out to 61 companies that have invested in incinerators across China to provide feedback, he said. Only one agreed to speak with them.

The head of a local organization in another city said officials asked him to effectively turn informant and report instances of environmental malfeasance directly to them rather than post about it on social media or talk to journalists. Tired of the group’s demands for investigations and transparency, the officials threatened to shut it down and revoke their license.

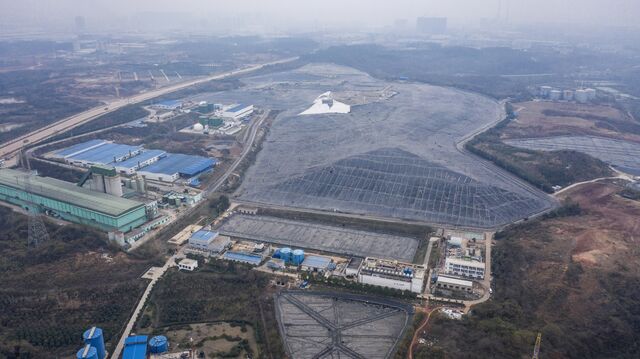

The result of stifling environmental activism can be seen in Wuhan. Home to a bustling port along the Yangtze River, the city has grown rapidly as China’s economy developed. The urban sprawl has made it harder to find locations for incinerators needed to dispose of the 12,000 tons of garbage produced daily by Wuhan’s 11 million residents.

The increasingly wealthy and educated middle class has little tolerance for harmful toxins that could taint the air and water—a fact mirrored across China that helps explain the central government’s anti-pollution focus. In Wuhan, the middle class is also distrustful of official pledges to ensure the incinerators are safe. After the 2014 protests, the authorities promised to increase inspections and a billboard was put up tracking pollutants emitted by the plant. The concessions did little to appease local residents, who say the readings aren’t reliable.

Last summer, protests broke out again, this time over a proposed incinerator in Yangluo, a suburb some 50 kilometers (30 miles) from Guodingshan, the district where the first banner was raised. According to media reports, police clashed with local residents who demonstrated for several nights. The plant was later suspended by the local government.

▼

In December, the site was overgrown with weeds and the red ground largely deserted. A worker gathered what few materials remained, saying he’d been told to put them away until a decision was made on whether to proceed with the project. He said he’d rejoiced at news of the plant’s suspension, adding that it should never have been built so close to habitation.

China’s environment ministry and the provincial government of Hubei—where Wuhan is located—did not respond to faxes seeking comment. Wuhan Environment Investment & Development Co. Ltd, which invested in the proposed incinerator in Yangluo, also did not respond to a fax asking if the project would go ahead.

One resident of a nearby village said there had been no public consultation or official announcement regarding the project. A grandfather who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, he said he opposed the plant because it would affect future generations.

Almost six years on from the first protests in Wuhan, many families with the means to do so have left, especially those with young children.

Ren Rui, 40, quit her apartment in 2017 after her son developed a lung condition that required repeat surgery. She said smoke from the plant would blow her way under certain conditions. She tried to rent it out, “but no one wants to move here.” “Sometimes my mood depended on the direction of the wind,” said Ren. Despite the financial pressure since, “I never regretted moving away.”

—With assistance from Sharon Chen and Dandan Li