The Coal Is Gone, But the Mess Remains

How big companies shed their obligations to clean up old mines.

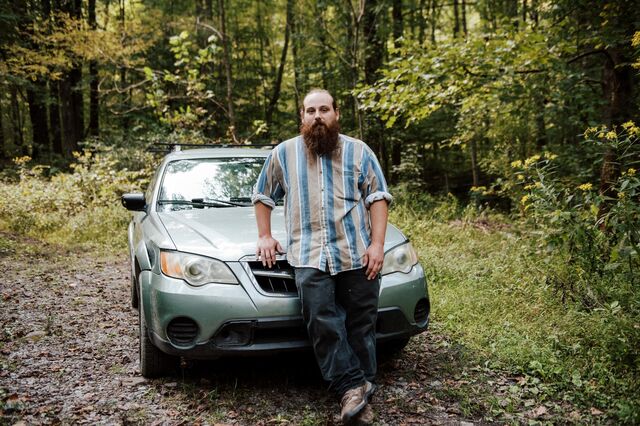

Miles Hatfield was walking into his dining room when he felt the wooden floor give way. His legs dropped hip-deep into water that had pooled under his brick house in the green hills of eastern Kentucky where he had lived for the past 40 years, trapping him in his own floor.

Hatfield, a retired coal miner, raised two boys in the house a few miles from the West Virginia border and added on five rooms as his family grew. But the red water that ran off from the nearby Love Branch coal mine had turned his backyard into a marsh, ruined his septic system and finally sucked him through his floor three years ago.

Love Branch used to be owned by one of the biggest coal companies in the US. Federal law requires companies to restore the land when they finish mining, and Love Branch hasn’t produced any coal in more than a decade. But the former owner, now named Alpha Metallurgical Resources Inc., transferred the mine and its cleanup obligations to a smaller company in 2018, the year before Hatfield fell through his floor.

“They pretty well destroyed me up there,” says Hatfield, 70, who had to move to a rental nearby. “Everything for me is gone.”

Coal Country

Three of the mines Lexington acquired from Alpha in the heart of Appalachia

Hatfield filed a complaint in 2018 with Kentucky regulators, who said Love Branch caused flooding on Hatfield’s property and at neighbors’ homes above Deer Lick Road. Lexington Coal Co., which now holds the permit, was fined $30,000 in June for failing to clean up the mine and stop the leakage. Lexington said in a July filing that it doesn’t admit responsibility for any damage and that it needs more time to finish reclamation, which requires returning the land to its original shape, planting vegetation and preventing future flooding or toxic runoff.

Alpha has transferred more than 300 mining permits to smaller companies since 2015, when an industry-wide downturn pushed it and other big coal companies into bankruptcy. By shedding those permits—more than it currently holds—the company also freed itself from the responsibility to clean up the mines. Those old Alpha permits are now owned by companies like Lexington, many of them in precarious financial shape. They also have drawn pollution lawsuits, environmental violations and complaints from distraught homeowners like Hatfield.

While coal’s devastating contribution to climate change has been well documented, it has also left a long and painful legacy in communities where it’s mined. A joint investigation by Bloomberg News and NPR found that Alpha is one of several large US coal companies that used the same playbook. They transferred old mines in need of cleanup to smaller operators with meager financial resources, raising the risk that taxpayers, rather than industry, will eventually be stuck with the cost. And the very weakness of these new owners limits regulators’ powers. Anything officials might do to enforce environmental laws—from issuing fines, halting coal production or revoking permits—could result in even less money to restore blighted landscapes.

The cleanup obligations held by just three of these new owners in multiple states amounts to more than $800 million, according to a Bloomberg analysis based on mine-permit data and per-acre reclamation costs contained in a West Virginia legislative audit. To guarantee their obligations, regulators have required the companies—Lexington, Blackjewel LLC, and ERP Environmental Fund Inc.—to post bonds of less than half that amount, leaving a potential shortfall of about $480 million, the analysis shows. Blackjewel filed for bankruptcy in 2019 and is currently in liquidation, and ERP has been in court-supervised receivership since 2020.

Meanwhile, billions more in retiree health and pension costs have been transferred to the federal government by companies that went through bankruptcy and are now profiting from a surging coal market. The United Mine Workers of America estimates that about $17 billion of liabilities are now mostly the responsibility of US taxpayers.

Alpha Kept the Coal and Left the Cleanup to Lexington

Lexington has more mining permits than any company in the US but produces little coal

Alpha said in a statement that it is proud of its environmental record and that the transactions were part of a transition from thermal coal, burned to make electricity, to metallurgical coal used to produce steel. “These transactions are subject to significant oversight, requiring the review and approval of a number of government regulators,” the company said. “In many cases, Alpha has included funding within such transactions for reclamation and other liabilities.” Lexington said it would answer questions from Bloomberg but didn’t.

For people who live near those idled mines, the flooding, the polluted streams and the damaged homes can be overwhelming. Hatfield says he hates writing rent checks after working decades to pay off his mortgage. He says Lexington paid him $1,500 for the right to drive onto his land about two years ago and bury a pipe that’s supposed to redirect all the water, but it hasn’t helped. And he’s not holding out hope that an Alpha or Lexington executive will offer to pay for a new floor. “I’d tell him I’d greatly appreciate it if they’d make things right,” Hatfield says. “He’d probably laugh at me because he knows he’ll get away with it.”

Coal is welded to the story of how the US became a superpower. It was used to forge weapons in the American Revolution, and, over the next two centuries, provided the energy that powered the nation. Along the way, coal companies destroyed millions of acres of productive land, left behind more than 50,000 underground mine openings and polluted thousands of miles of rivers and streams. But there were no federal laws requiring them to mitigate the damage.

A turning point came in the 1920s, when the Pennsylvania Railroad sued a coal company to stop it from dumping so much acid into a creek that the water couldn’t be used in its steam-powered trains. The state’s top court ruled in the railroad’s favor.

Another 50 years would pass before Congress passed the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, creating federal minimum cleanup standards and a bonding system to help cover the costs if companies walked away from their obligations. From that point on, coal companies were supposed to restore land as they mined.

Joe Pizarchik, who ran the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement during the Obama administration, says the law eliminated almost 50,000 underground mine openings and more than 1,000 miles of dangerous cliffs left behind by coal companies.

Most states came to administer their own regulations and reclamation efforts, with varying degrees of enforcement. Pizarchik remembers one Pennsylvania regulator he worked with who had a memorable method for determining whether it was necessary to reclaim a stream. “If he could piss across it, it wasn’t worth protecting,” Pizarchik says.

But as coal companies began struggling to compete with cheaper natural gas more than a decade ago, they started offloading their cleanup obligations. Alpha would follow that same strategy.

Alpha was a creation of private equity. First Reserve Corp., a leveraged buyout pioneer based in Connecticut, spent $260 million in 2002 to buy three coal companies. First Reserve didn’t plan to stay in coal long, announcing it would boost profit and sell the company. “We're picking stuff up at wreckage prices from people who are getting out of the business,'' Chief Executive Officer William Macaulay said at the time.

First Reserve kept its promise. By 2006 it had taken Alpha public and sold its ownership stake. A 2005 filing showed that First Reserve owned about 26 million shares of Alpha, or 43% of the company, then valued at $740 million. That meant the private equity firm made almost half a billion dollars on the deal. First Reserve declined to comment.

Over the next five years Alpha kept buying, culminating in its purchase of Massey Energy Co., the biggest coal company in central Appalachia. Massey had been shaken by a 2010 explosion that killed 29 people, the worst US coal mining disaster in 40 years. Alpha paid $7 billion for Massey less than a year later.

New Owners for Old Mines

Hundreds of idle coal mines have been transferred from the biggest producers to new owners with little or no production

By early 2015, the amount of US electricity produced by gas overtook coal for the first time. One by one, the giants began to fall. Patriot Coal Corp., created from mines spun off from larger companies, filed for bankruptcy in May 2015. Alpha filed that August, and Arch Coal Inc. followed in January 2016. Then bankruptcy came for the world’s biggest private-sector coal company, Peabody Energy Corp., whose record of environmental damage was memorialized by singer-songwriter John Prine. Arch and Peabody didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Josh Macey was a Yale Law School student at the time. He had worked in finance before getting interested in the environment, and the combination of the two led him to pore over the cascade of bankruptcy filings. The result was “Bankruptcy as Bailout,” an article he co-wrote for the Stanford Law Review that described how the four coal companies used the federal bankruptcy system to shed billions of dollars of environmental and labor liabilities.

US bankruptcy law aims to get foundering companies back on their feet by canceling debts they have no hope of paying. But critics like Macey, now a law professor at the University of Chicago, say the code is ill-equipped to deal with obligations imposed by labor or environmental laws. These can get short shrift in bankruptcy, Macey wrote in the article, allowing companies to essentially use the courts to invalidate regulations they don’t want to follow. When coal companies shift their old mines to shaky owners, he went on to argue, those transactions should be viewed as fraudulent transfers—the technical term for moving assets in order to stiff creditors.

“This is a slight exaggeration,” Macey says in an interview, “but it’s like they say, ‘I'm going to give all these liabilities to my destitute neighbor.’ You can't imagine that cleanup will actually happen.”

When Alpha reached bankruptcy court, stockholders were wiped out and bondholders took billions in losses. But its top creditors, including JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s Highbridge Capital Management, were adamant that the company terminate its union contracts and worker benefits, too. Judge Kevin Huennekens approved the plan, which freed Alpha from $1.2 billion in pension obligations and $1 billion in healthcare costs, the United Mine Workers of America estimates. Alpha also shed an additional $494 million in black lung benefits, according to the US Government Accountability Office.

Alpha said in a statement that it follows legal and regulatory guidelines and conducts its business in an ethical manner. JPMorgan declined to comment.

If coal companies abandon their black lung obligations, the federal government picks up most of the bill. The government also covers most of the unpaid pension liabilities and other healthcare benefits promised to miners. A bill introduced by West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin and passed in 2019 lifted the amount of taxpayer funds that can go toward those payments to $750 million a year.

Broken Promises

Coal company liabilities shed in bankruptcy and mostly assumed by US government

But even after shedding more than $2 billion in labor obligations, Alpha still had a problem: Regulators objected to a plan for its lenders to take ownership of the company’s productive Wyoming mines while leaving hefty reclamation costs in a separate company. “Alpha cannot simply walk away from those obligations,” the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, or DEP, said in objecting to the plan.

Regulators and environmental groups weren’t the only ones sweating. A group of insurance companies were on the hook if there were shortfalls in the cleanup plan, and they complained at a hearing that Alpha wasn’t sharing details of its expected costs. “This company is not a reclamation company,” an Alpha lawyer shot back. “It’s a coal company.”

Alpha eventually worked out a deal with West Virginia and other states where it operated. The company would be required to fully reclaim all of its sites, setting aside more than $300 million in special accounts for that purpose and also agreeing to kick in half of its free-cash flow until the work was completed.

Trouble started soon after a judge approved the plan and Alpha emerged from bankruptcy. Company executives revealed that a math error had inflated projected cash flow by $100 million, which meant less money would be available upfront for cleanup than they had let on. West Virginia complained in court that it had been duped, but acknowledged it was too late to unwind the plan.

Not long after, Alpha announced another change. Rather than do the cleanup work itself, it handed off idle mines and more than $300 million in cash and installment payments to Lexington, a much smaller company with little exploitable coal. Instead of an open-ended commitment to pay whatever was required, Alpha’s obligations were now capped. Alpha’s CEO said the deal would accelerate the cleanup. His counterpart at Lexington spoke in a statement of a “five-year timetable” for reclamation.

Five years have passed, and signs of progress are scarce. Of the 232 permits Alpha transferred to Lexington, only 41 have been fully cleaned up, state records show. By another measure, Lexington is doing even worse: Of the $190 million of bonds regulators required it to post to guarantee reclamation, they have authorized the release of just $24 million, or about 13%, according to state data compiled by Bloomberg and by Appalachian Voices, an environmental advocacy organization.

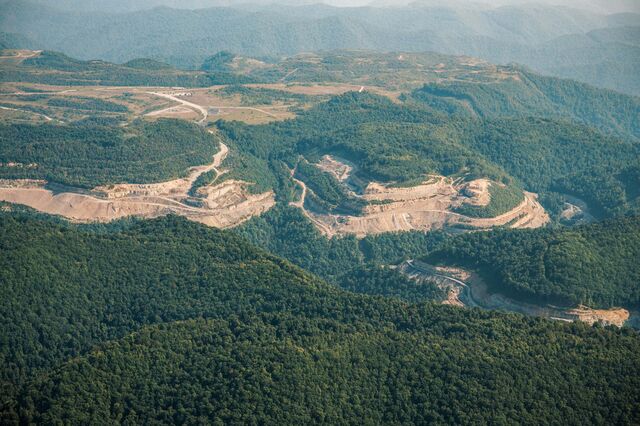

Junior Walk sees that unfinished work every day. The 32-year-old environmental activist with Coal River Mountain Watch spends his days driving an old Subaru along back roads in West Virginia and flying drones to peer down on the gray moonscapes created by strip mining. With a black Glock strapped to his hip, he patrols thousands of acres once mined by Alpha. His reports have prompted unannounced inspections and kept regulators focused on reclamation issues.

Walk came by his distrust for coal companies early: As a boy in Raleigh County, he watched his grandfather make jack rocks, small metal objects with a spike sticking up that were used by miners in labor battles to puncture car tires. He says he couldn’t drink the water in his own home as a teen because of mine runoff, and he isn’t hopeful that Alpha or any other company will step in to make things right.

“These billion-dollar corporations are going to do whatever they want to do because they own the state,” he said one day in July, as leafy branches slapped the dirty windshield of his car bumping up a steep dirt road in southern West Virginia. “And what they want to do is whatever’s cheapest for them and worst for us.”

Near the top of the mountain, he pulled the car off the road, eyed the grass for rattlers, then snapped the propellers onto his drone. It rose with a loud buzz and was soon looking toward the Twilight complex across the valley, a collection of surface mines now owned by Lexington with a circumference of more than a dozen miles.

Lexington is actively mining coal at Twilight and has racked up more than 20 violations there, including dumping so much dirt into a stream that muddy water could be seen from “bank to bank” seven miles downstream. The nearby Crescent mine, which it also took over from Alpha, has been the subject of more than 30 violations and about $50,000 in fines for failing to control runoff and letting boulders roll downhill to damage trees. In August, state regulators ordered Lexington to explain why its Twilight and Crescent permits shouldn’t be revoked.

The company was issued 53 state and federal violations this year through mid-June, more than all but one other miner in the US, a federal database shows. That’s up from 31 in the same period last year. In September, state regulators took the extreme step of suspending Lexington’s Crescent permit. And the federal judge overseeing a lawsuit accusing Lexington of polluting streams and rivers at two other mines told the company he was “losing patience” with its lack of progress and imposed a $1,500 a day fine.

Lexington’s Violations

Since taking control of mines from Alpha in 2018, Lexington has been issued more than 200 state and federal environmental violations

Regulators in West Virginia and Kentucky defended their decisions to allow Alpha to shift its cleanup obligations to Lexington, pointing out that they have limited powers to block transfers if applicants meet basic requirements. The Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet noted the transfer took place amid a “severely depressed coal market.”

If a coal company goes broke, states have two layers of backup funding available to pay unmet cleanup costs. The first is the bond companies are required to post as a condition of mining, typically backed by an insurer, though some states, including West Virginia, don’t require bond amounts that cover all anticipated costs. The second is the state reclamation fund, typically supported by a tax on coal. Only if both of those sources run out is there a risk taxpayers will have to foot the bill for an abandoned mine.

The West Virginia DEP said that taxpayers aren’t at risk of having to pay for abandoned mines because the reclamation fund would cover any shortfall. Not everyone is so confident. A report last year by West Virginia legislative auditors warned that the cost of abandoned mine permits could exceed the reclamation fund by hundreds of millions of dollars, eventually threatening to stick taxpayers with losses.

Lexington said in a letter to Coal River Mountain Watch last year that it believes environmental stewardship is integral to coal mining and that it strives for full compliance with environmental regulations. “The majority of Lexington’s active work company-wide is reclamation,” it said.

Alpha offloaded mines that were later acquired by other companies with leaders who have been accused of wrongdoing or a history of environmental violations. More than 30 permits in Virginia and Kentucky were transferred to an affiliate of Blackjewel, which then went bankrupt. They were later acquired by a company whose president, Hunter Hobson, was arrested this year on unrelated charges that he bribed a coal company in Egypt. (He pleaded not guilty, and his lawyers didn’t respond to emails seeking comment.)

About 40 more permits went to Pristine Clean Energy LLC, which has racked up more than 400 unresolved violations of federal and state laws, among the most of any miner, a federal database shows. In September, a judge fined the company about $650,000 for discharging selenium from one of its mines. Lawyers for the company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Selenium is vital in small amounts, but in higher concentrations it becomes toxic for animals that lay eggs, such as insects, fish and birds. It causes deformities including bent spines, misshapen jaws and eyes in the wrong places. Selenium builds up in the bodies of spiders that eat the bugs and in the birds that eat the spiders. Some of the highest concentrations of the element ever recorded in wildlife came from samples taken near coal mines in West Virginia.

Selenium is just one of the threats to Appalachia, home to one of the oldest and most biodiverse mountainous ecosystems on Earth. Left untreated, some streams near mining areas are laced with sulfuric acid, salts and metals such as aluminum and iron, which turns the water orange.

Emily Bernhardt, a professor of biology at Duke University, estimates that 30% or more of the river networks in one section of West Virginia are now too degraded to support the most sensitive species found there. “The people living in this once-beautiful landscape,” she says, “are now living in a landscape that is really, really altered.”

Halfway between Musick and Pie in rural West Virginia, about 30 miles from the Twilight mine, Gary VanNatter lives alongside a burbling brook. VanNatter, a former coal miner, was used to seeing runoff from the idle mines up the road. But he wasn’t prepared for the flood of orange-colored water that filled his garage ankle-deep one day in July.

“It was coming down like a raging river,” VanNatter, 36, says a few days later, backing a black pickup stacked with waterlogged wood out of his driveway. “I’ve never seen it that bad.”

The nearby Mountaineer mine used to be owned by Alpha, but instead of cleaning up after coal production finished there in 2013, Alpha transferred it to Lexington. A state regulator’s report in May found that four of the six pumps used to control water levels at the mine weren’t working and said Lexington was responsible for one homeowner’s well overflowing. The high waters inside Mountaineer flow into a connected underground mine owned by another company that overflowed and damaged nearby properties, according to state documents.

Slow Cleanup

Alpha transferred a group of mostly idle mines to Lexington in 2018. Work to restore land and water has been completed on less than 20% of permits

VanNatter and 10 of his neighbors sued Lexington and the other company for allowing water to pour out of the ground and damage their homes. Lexington denied in court filings that it is responsible for any flooding or damages. State regulators said the company didn’t follow its pumping plan but that the other company was more responsible for the impact on homes.

“It’s sinking my foundation,” says VanNatter, who worked for Alpha about a decade ago and has lived in the area his entire life. “If I have to leave here, man, that’s gut-wrenching.”

Unreclaimed or active coal mines can also worsen flooding during intense storms, with more water flowing through areas with surface mines compared with unmined areas, according to a 2011 study by the US Environmental Protection Agency. And scientists predict that climate change will bring torrential rains more often. After floods struck Eastern Kentucky and killed 40 people in July and August, some residents of Lost Creek sued the coal company that mines the land above their town for making the flooding and damage worse.

All these old coal mines present a looming and potentially expensive disaster for coal country—and for taxpayers who could be on the hook. Meanwhile, Alpha’s share price has gone up more than 700% since it exited bankruptcy in 2016. The executives who guided the company through bankruptcy, a corporate split, a re-merger and a name change have been handsomely rewarded. Kevin Crutchfield, CEO from 2009 to 2019, earned at least $72 million in those years. President Andy Eidson, set to take over as CEO, has made at least $16 million since he joined Alpha a decade ago.

Environmental advocates say big coal companies transfer their mines and reclamation obligations to save money, despite the cheery confidence they express in the ability of new owners to clean up their messes. Indeed, Alpha and Lexington both trumpeted their commitment to reclamation when the deal was announced.

“It’s a fig leaf,” says Erin Savage, a scientist at Appalachian Voices in Boone, North Carolina. “It comes down to the math.” Alpha and other large coal companies must know that reclamation would cost them more than they pay to the company that takes the mines off their hands, Savage says. “Otherwise, why would they do it? They’d just do the reclamation themselves.” —With Scott Carpenter

This story was reported in collaboration with NPR, which is airing several radio broadcasts on the subject.