A Farewell to the Hong Kong I Loved

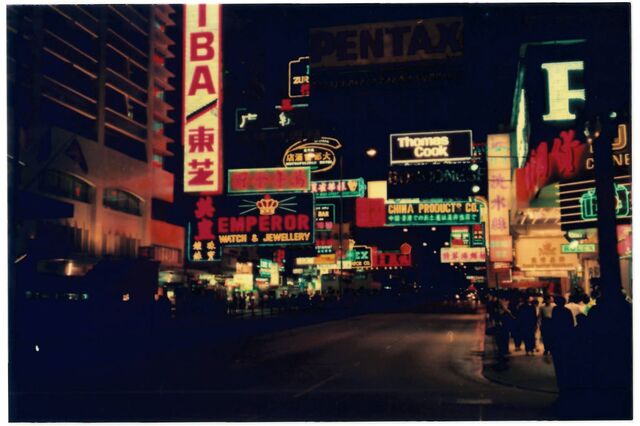

It rained for much of April 1992 in Hong Kong. Outside the shabby guesthouses of Nathan Road, the neon-lit artery that bisects Kowloon, the muggy spring air hung in a permanent haze. The wooden scaffolding that cobwebbed the building facades dripped constantly, giving the nights a dystopian atmosphere.

Like many people, I arrived somewhat by accident — a bored and restless 28-year-old British journalist who got halfway through a round-the-world trip before running out of money and heading to the nearest place that offered the chance of making a living.

Since the 19th century, Hong Kong had been attracting buccaneers, wanderers, refugees, spies and ne’er-do-wells. Many stayed. “Hong Kong is full of people who came here for six months 25 years ago,” one long-term resident told me shortly after my arrival. As of 2017, I could count myself among them. We all washed up on what Han Suyin called this “excrescence” off the coast of China, some in search of adventure and economic opportunity, some simply looking for shelter from instability and persecution, from across the border in mainland China, or further afield.

A few weeks after landing, I was in a bar listening to a self-professed gun runner talk about flying plane-loads of money into Caribbean islands. With mocking derision, my interlocutor (his name forgotten, if I ever knew it) described the lax customs procedures for those who arrived there with bags of cash: “Where has the money come from? A bank. Where is it going to? A bank. And then they say, ‘but we have forms!’” he shouted, waving his arms in the air. Was any of it true? I have no idea.

It was that kind of place, though. Hong Kong “was founded on contraband and conquest,” as the Australian journalist Richard Hughes observed in the 1960s, in his introduction to the “rambunctious, freebooting colony.” Hughes himself was a reputed spy, a fixture at the Foreign Correspondents Club and the model for the character of Old Craw in The Honourable Schoolboy, John le Carre’s 1977 spy novel set in the territory. In the dying days of empire, a whiff of that disreputable past still hung about the place.

Hong Kong was far from perfect. The apartments were tiny. The weather was intolerable for a good part of the year. The noise was incessant, and the crowds were ever-present. The people were mostly indifferent to outsiders, and sometimes borderline hostile. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, it was the most imperfect place I had ever lived, except for all the others.

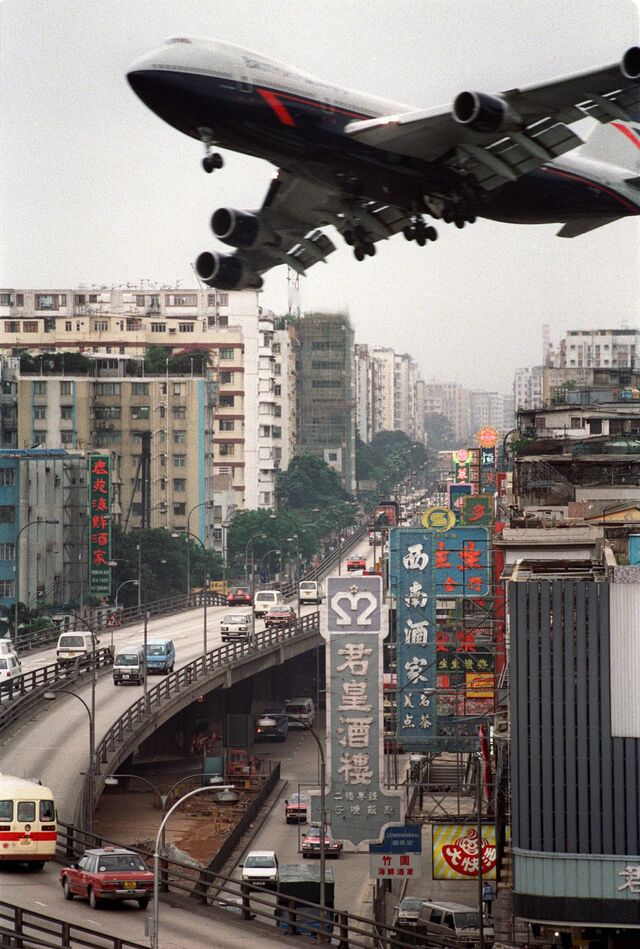

It had energy, and spirit. The city brimmed with nervous tension. Five years before the U.K. handed the territory back to China, everyone seemed to be in a hurry — to make money, to gain a foreign passport, to move up or out. After recessionary Britain and the bland conformity of Australia (my last stop before Hong Kong), it was intoxicating. I felt instantly at home. The city’s unsettled mood perhaps matched my own.

Now it is 2020. In this year of so much death, so many grim landmarks, the curtain has fallen with startling rapidity. I mourn for the extinguishing of an exuberantly free society that, over three decades, taught me so much: about resilience, pragmatism, humor, adaptability and optimism.

Hong Kong’s extremes of wealth are well documented. Perhaps nowhere else do rich and poor live quite so cheek by jowl. Things moved fast. Fortunes could be made — and sometimes lost — quickly, particularly in the property market.

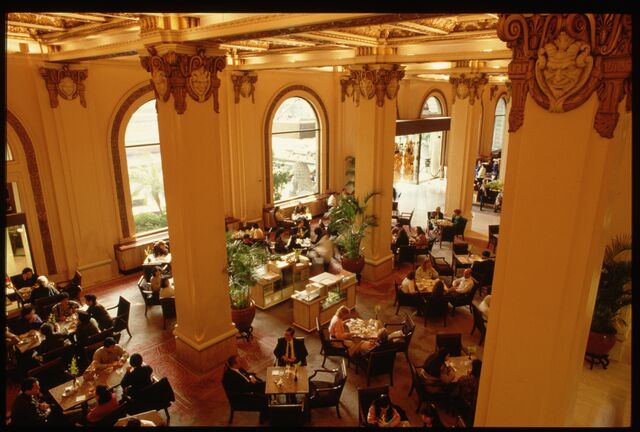

My own small experience of this economic fluidity was going within weeks from a dormitory bed in Chungking Mansions to lunch at the Peninsula Hotel on the other side of the road. One was a rundown, labyrinthine warren of budget hostels, cheap curry houses and purveyors of fake Rolex watches — the other, a few paces away, the five-star “grand old lady” of Hong Kong. In this city, discrete worlds exist almost on top of each other. For someone who’d been living on HK$2 (26 cents) packets of instant noodles from the 7-Eleven, the incongruity of staring at a menu full of HK$100-plus options left a deep impression (it was a business lunch, and I wasn’t paying).

Hong Kong was a challenge on a backpacker budget. If I hadn’t found work, I would have needed to leave quite quickly. In retrospect, that wasn’t very likely.

Economic volatility goes with the territory. In 1992, Hong Kong was starting to boom. Earlier in the year, Deng Xiaoping had carried out his famed “southern tour,” signaling an end to the post-Tiananmen freeze and a return to economic reform. The U.S. had emerged from recession, and in November elected a new president in Bill Clinton who ushered in a long expansion. As an externally focused economy with a currency linked to the dollar, Hong Kong was like a small boat tossed on the seas of global vicissitudes. Right now, it was rising on the waves. The Saturday newspapers bulged with classified advertising.

The city’s sometime reputation as the world’s freest economy has always been as much myth as reality. Hong Kong’s domestic economy is beset with monopolies and cartels; low tax rates are counterbalanced by high property prices that act as an indirect levy; more than 40% of the population live in public or state-assisted housing.

For all that, the city is a case study in what can happen when a government establishes a basic structure — rule of law, relatively clean administration, a minimum of red tape — and then stands back and leaves people alone to get on with it. The evidence is that a lot of energy is released. The hundreds of thousands who poured across the border from China to escape the 1949 revolution expected little, and for the most part got nothing. The thriving and ultimately wealthy industrial center they created wasn’t the product of government design. The colonial administration had little interest in directing people’s lives. There were no engineers of the soul in Hong Kong.

The concept of laissez-faire, or benign indifference, looks at this point as anachronistic as the 19th century or Margaret Thatcher, after decades of widening global inequality and rising social discontent. This very much includes Hong Kong itself, which finally brought in a minimum wage in 2010. Yet the philosophy did much to shape the character of the city’s people.

As a foreigner with a British passport, I entered with privilege. Many Hong Kong Chinese had a more tortured passage. My first wife arrived as an illegal immigrant, aged seven, on a boat from Taiwan: a very Hong Kong story, even if she didn’t swim the Shenzhen River to get here.

She was sent to live in a dormitory in Rennie’s Mill, a former refugee village for Kuomintang followers who had escaped from the mainland after the Communists won the civil war, and which thereafter became the de facto Taiwanese enclave in Hong Kong. I live there now, amid a forest of 50-story tower blocks. The area has been developed into a new town. The squatter camp is long gone, cleared out before the handover; it wouldn’t have done for the British to return a territory containing a pocket of flag-waving Nationalists. Times move on.

In the 1990s, like most people, my then-wife generally avoided speaking Mandarin on the street, despite being fluent. This was an act of self-preservation. It was the language of the poor country cousins across the border. Speaking it publicly advertised one as belonging to a lower rung in the social hierarchy, in a status-obsessed city. For complaints, English was best.

“Almost from the start everyone looked down on everyone else,” the Welsh writer Jan Morris observed of Hong Kong. “Henry T. Ellis, a naval officer in port in 1859, defined the general social attitude of Hong Kong as one of ‘purse-proud stuck-upism’, and the definition has never been out-dated.”

The colonials set the template, then. The vein of snobbery and money worship that ran through Hong Kong society was the natural accompaniment to the disinterest bordering on disdain shown to outsiders. Over time, this jarred less. I learned to stop taking it personally. It was an equal-opportunity snobbery, applied to all who weren’t Hong Kongers. On occasion, such as after an encounter with a particularly irascible taxi driver, it could feel like Hong Kong people didn’t like anyone very much, including each other.

To understand all is to forgive all, as the French proverb goes. What I perceived initially as unfriendliness started to appear more like simple brusqueness. Hong Kong manners were the product of its refugee past. Many arrived in the city with nothing. They had to struggle to get there, then to survive, and perhaps just to assert their right to exist amid an unwelcoming native populace. They had to live on their wits and had little time for small talk. If they had come through such testing circumstances, supported only by self-reliance, was it any wonder that some were a little proud, and adopted the manners of the club they had joined?

The place I have been in the world that most reminds me of Hong Kong is New York, another city whose character owes much to its immigrant history. Both have that burgeoning vitality combined with a don’t-mess-with-me pugnaciousness. And underneath that calloused exterior, an unexpected kindness can often be found.

The eagerness to distance from their mainland roots has always carried a layer of self-conscious irony. In the pre-handover film Comrades: Almost a Love Story, Maggie Cheung plays a streetwise, money-focused and Cantonese-speaking mainland immigrant who takes callow northerner Leon Lai under her wing, patronizing, exploiting and ultimately falling in love with him. The sting in the movie’s tail is the final scene, which reveals that the couple arrived in Hong Kong not only at exactly the same time, but on the same train. Cheung has simply been quicker, and more willing, to adapt.

In any case, politics aside, Hong Kong has lost some of its rough edges — and much of its dynamism — as the city (if not all its people) has become richer, and more educated. Or perhaps it just seems that way because I no longer consider myself an outsider — although in one important respect, I remain excluded.

If I have a regret, it is failing to master Cantonese. The humor and vivacity of Hong Kong’s people find their fullest expression in the language. Cantonese is rich in homonyms, making it ripe for puns and word play — and the vehicle for a culture that prizes satire, irreverence and mockery.

I’m not a gifted linguist. After two years of glacial progress, I essentially gave up. An abiding memory was the repeated experience of trying to use words in class that I had learned studying on my own. “Ha ha ha! What did you say?” I lose count of how many times I heard this as my teacher ripped the textbook from my hands. “Oh no, we don’t talk like that anymore. We say this…” The book I was using was little more than a decade old at the time. Spoken languages change fast. It was like trying to hit a moving target.

Even a newcomer could get a sense of the exultant liberation that pulsed through Hong Kong’s language, though, if only via translations of the city’s viciously competitive media. It could be coarse, as well as playful. It was scornful of authority, profoundly democratic. Jimmy Lai, proprietor of the best-selling Apple Daily newspaper and Next Magazine, is renowned for having insulted then-Chinese Premier Li Peng as a “turtle’s egg” in an editorial in 1994, a decision that led to the forced sale of his stake in the Giordano clothing chain, which had many outlets in mainland China. A former Hong Kong financial secretary who bought a car shortly before raising the registration tax earned the moniker “Lexus Leung.” More affectionately, though with no greater deference, the last British governor of Hong Kong, Chris (now Lord) Patten, was known as "Fat Pang." It was a radical contrast to the system in mainland China, where state TV broadcasts still read out lists of officials attending events in dutiful order of seniority.

The media mirrored the nature of the people. In 2000, then-Chinese President Jiang Zemin, unused to the blunt questioning of an unfettered press, angrily berated a Hong Kong journalist in English as “too simple, sometimes naïve.” To this day, “too simple, sometimes naïve” remains a favorite jibe between Hong Kong friends, a gleeful reminder of the territory’s subversive ability to puncture the pomposity of overbearing officialdom.

The unpopular former Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying received similar treatment. At some indeterminate point, Ikea in Hong Kong started selling a toy wolf called Lufsig. By unfortunate (or serendipitous) coincidence, the name in Cantonese sounded like a crude phrase with sexual connotations. Leung had long had a reputation as a wolf — a cunning political operator with disguised intentions. When an anti-government protester threw one of the stuffed toys at the chief executive in late 2013, a citywide craze was born — one that managed to combine two perennial Hong Kong hobbies: queuing for collectibles and showing disdain for the government. Lines formed, and Lufsig quickly sold out. Ikea said it regretted its choice of name and changed it. (Leung responded by posing with one of the toys on his desk and praising Hong Kongers’ creativity.)

Having despaired of Cantonese, I made a more sustained effort much later to learn Mandarin which, for reasons too numerous to list, I found far easier. My second wife is from northeast China. Though we have gravitated toward English, I can still hold a conversation in Mandarin, if a little awkwardly. I’m proud of that limited accomplishment. Yet when I hear a table of Cantonese friends making each other shriek with laughter, I still feel I have missed out.

So we come to the close of a tumultuous year. Jimmy Lai is in prison, along with Joshua Wong and other activist leaders; even moderate pro-democracy politicians are fleeing abroad. The handover that everyone feared, the driver of the frenetic activity that I saw in 1992, has finally arrived. It just came 23 years later than many people expected. In retrospect, the past two-and-a-bit decades seem like an interregnum, an unofficial extension before the new power declared itself.

There’s no denying that Hong Kong has an ugly, nativist side. I deplore the animosity toward mainlanders. The people are not their system. But neither do I believe these fringe elements represent the soul of Hong Kong, which I associate with an outward-looking attachment to universal values of freedom, individual dignity and justice. If you were to attend the huge, solemn and dignified Tiananmen vigils held annually in Victoria Park by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, you would see a different, understated side: one that is civic-minded, politically conscious and historically aware. (The vigil was banned this year for the first time in three decades, ostensibly because of the pandemic. Several thousand turned up anyway.)

Perhaps we all do this with the places we love: take the attributes with which we identify and discard the rest. When I think of what makes me proud to come from Britain, I think of the Beatles refusing to play in front of a segregated crowd in the U.S., for example, or the National Health Service surgeon who spent an hour talking to me after performing an emergency life-saving operation on my son at 4:30 a.m. I don’t think of Brexit.

Why mourn in any case for a former colony that for China is the reminder of a historic crime? In fact, these contradictions and paradoxes only heighten the feelings of identification. Hong Kong as an entity distinct from mainland China was the product of an act of international piracy yet became for a while perhaps the place in China that was most stable and orderly, and where people were the most free. Denied real democracy under the British and then under Beijing, it is the most democratically minded of societies. Flowers grow in compost; the darkness shows up the light.

The first days of that rain-soaked April come back to me now, like a premonition of encroaching darkness. The neon gloom of Kowloon in 1992 reminded me instantly of Blade Runner, a favorite movie. A few years ago, I introduced Ridley Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece to my elder son and got a jolt when I heard Cantonese being spoken, realizing that I not only recognized but understood some of what was being said. It was another marker of how I had travelled.

“All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain,” the doomed replicant Roy Batty says in the film’s melancholy climax. It has frequently seemed like that this year, as a program that feels like an attempt to erase everything that made Hong Kong what it was has advanced on multiple fronts. Yet as the year closes, I am not so sure.

The values that Hong Kong represents, and the people that carry the torch for them, won’t be so easily crushed. The love of freedom, and the unwillingness to submit meekly, run too deep in Hong Kong’s DNA. The younger generation, with its radical departure from the tactics of pro-democracy elders (however misguided and self-defeating some might argue that departure to have been), has already demonstrated that. And those values are imperishable, having endured across cultures and millennia. At the very least, it will take time.

There is still sadness, though. Hong Kong will never go back to what it was, that much seems clear. Its fate will be dissolved into a larger destiny, as was always likely and perhaps inevitable. My poor adopted city. Designed for obsolescence but wanting more life, it did burn so very brightly.